The Hospital Text Message That Sparked Confusion

If a stranger asked for your name, birth date, address, and email over text — would you reply?

That’s the situation many New Zealanders found themselves in recently, thanks to a public health campaign that might have been legitimate, but looked and behaved like a scam.

This isn’t about fear. It’s about designing trust — and how badly we fail when we don’t.

Confusion over text messages.

What Happened

As part of a national effort to validate outpatient waitlists, Te Whatu Ora began texting patients to confirm if they still needed surgery. The problem?

The messages:

- Came from unverified NZ mobile numbers

- Asked for sensitive personal details (name, DOB, address, email)

- Contained no clear sender identification or verification links

- Were not preceded by any advance notice or opt-in consent

To many recipients, it looked exactly like a scam. And in a parenting group we monitor, it triggered a flurry of confusion, concern — and contradictory advice.

Some replied with their details. Some ignored it. Some posted screenshots asking for help. Many were left feeling unsure, anxious, and mistrustful.

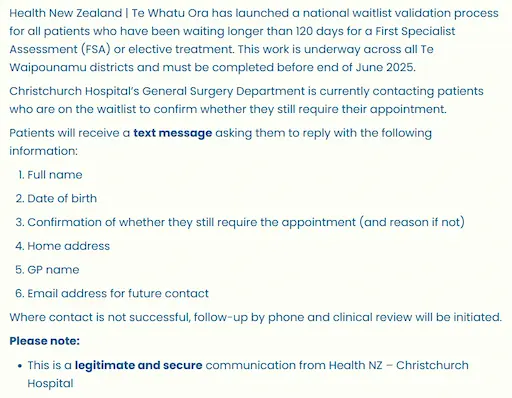

Wording on the official Te Watu Ora/Health NZ website

Why It Matters

Let’s be clear: this might have been a legitimate message from a public health authority. But the way it was delivered made it:

- Indistinguishable from a phishing attempt

- Easy to spoof. Any bad actor with a burner SIM could send the exact same message

- And damaging to the trust we rely on in health systems

- This is normalising replying to unverified messages with personal information

When real messages behave like scams, we all lose.

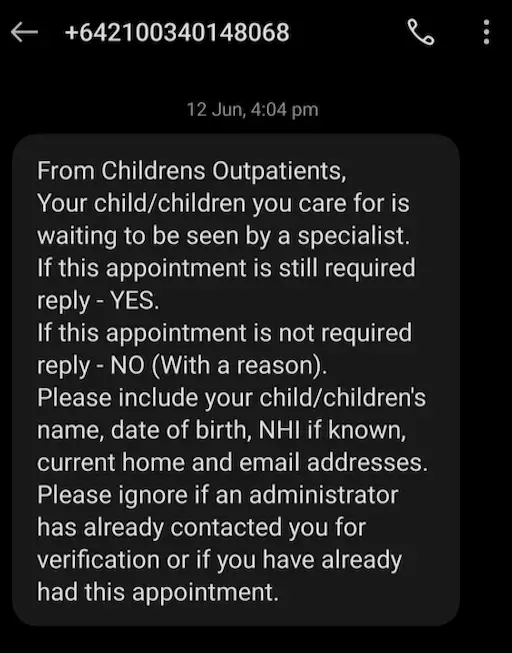

Example of an ‘offical’ text message.

Let’s Break It Down

Here’s what went wrong — and why it’s not just a “comms issue” but a privacy failure:

1. No Verified Sender

Most recipients received messages from random NZ mobile numbers (e.g. +6421…). That’s exactly how scammers operate. There was no shortcode, no registered SMS ID, no verification link. Just a vague message asking for personal data.

2. Sensitive Info via SMS

The messages asked people to reply with their full name, date of birth, address, and email. That’s a goldmine for identity theft — and SMS is one of the least secure ways to transmit it.

3. No Consent or Context

Recipients weren’t told ahead of time that this outreach was coming. There was no prior communication, no opt-in, no secure digital channel offered. The message just arrived, out of the blue, asking for details. Note: One user on Facebook said they had advertised this but I have not seen any advertisments and no one else confirmed this.

4. Inconsistent Format

Some messages included a callback number. Some didn’t. Some mentioned “you or someone in your care about,” others didn’t. Inconsistent language increases confusion — and opens the door for malicious copycats.

5. No Independent Way to Verify

There was no link to an official webpage. No “learn more” button. No way to confirm the message was part of a real campaign. People were left to Google, ask Facebook groups, or call overloaded hospital switchboards.

The Public Did the Right Thing

Here’s what stood out most in the responses we saw:

- People paused and questioned it

- They sought peer validation before replying

- Some called their hospital to verify

- Others held off completely — not out of fear, but because they were cautious

That’s exactly what we should be encouraging.

Unfortunately, this rollout penalised those instincts. It trained people to:

- Respond to vague messages

- Trust unauthenticated numbers

- Normalize insecure information sharing

That’s not just bad design. That’s training people to fall for scams next time.

Link to official site update: www.tewhatuora.govt.nz

Note: Just because some of these messages appear to be a genuine attempt to contact patients that doesn’t mean the one you receive is from a valid source. Please verify all messages before replying to anything - this unforunately means probably calling the hospital to confirm at this stage

A Final Thought

You shouldn’t need a background in cybersecurity to know whether to reply to a hospital text.

And when the message comes from your health system — you should never be left wondering if it’s real.

This rollout was sloppy. It was risky. And it was a missed opportunity to lead with privacy, clarity, and care.

In the next post, we’ll unpack the red flags in more detail — and explain why even legitimate messages can still be dangerous when privacy-by-design is ignored.

Want to be notified when it drops?

Join the Privacy Bootcamp or follow us on Facebook.