What Makes a Message Look Like a Scam (Even If It’s Not)

“It’s not a scam — it just looks exactly like one.”

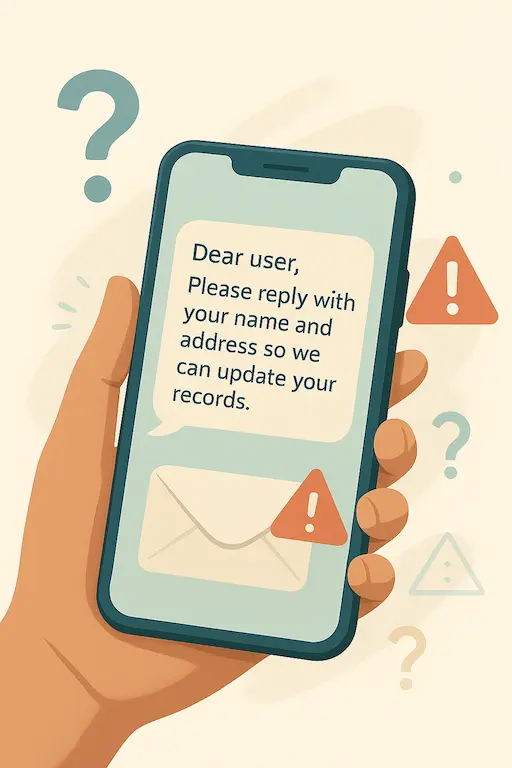

In this post, we’re breaking down why the messages triggered scam alerts in so many people — and why intent doesn’t excuse design that erodes trust.

Could you tell the difference?

🔍 Real Message, Scam Behaviour

Here’s a summary of the key patterns that made this SMS rollout indistinguishable from a phishing attempt:

1. Unknown Sender

The messages came from generic NZ mobile numbers (e.g. +6421…), with no identifying information in the contact or sender ID.

There was:

- No hospital name

- No shortcode

- No official SMS header or verification

This is how most SMS-based scams are sent — especially ones trying to appear local or urgent.

2. Requests for Sensitive Personal Info

Recipients were asked to reply with:

- Full name

- Date of birth

- Home address

- Email address

- NHI number (if known)

Not passwords. But this is exactly the kind of data used in identity theft, targeted fraud, or social engineering.

Worse, SMS is not encrypted. If you reply, your message could be intercepted, mishandled, or stored insecurely.

3. No Verification Path

There was no link to an official page, hospital website, or government site where the message could be verified.

Some people called their hospitals manually and confirmed it might be legit. That’s not good enough.

A message that can’t be independently verified is a message that shouldn’t be sent.

4. Unexpected Timing, No Consent

Many recipients weren’t expecting any message from public health.

Surprise + ambiguity + data request = classic scam feel.

⚠️ The Trust Pattern Is Broken

Good messaging — especially from public systems — follows a pattern:

- You know it’s coming

- You know who it’s from

- You know how to confirm it

- You can control how you respond

This campaign failed every part of that pattern.

And when people pause and ask, “Is this real?” — they’re not being paranoid. They’re doing exactly what we’ve taught them to do.

✅ What This Teaches Us

This is the real takeaway: “legit” isn’t good enough.

If your message looks, sounds, and behaves like a scam, it will be treated like one — and that’s on the sender, not the public.

When a real message mimics a scam, people don’t trust you.

When it comes from a public health agency, that mistrust doesn’t just hurt engagement — it damages the system.

This wasn’t a phishing attack. But it taught people the wrong lessons:

- That it’s normal to respond to unverified numbers

- That it’s fine to hand over personal details via plain SMS

- That it’s on you to figure out if a message is real or not

That’s not safe. That’s not ethical. And it’s definitely not privacy by design.

Coming next:

We’ll talk about how this could be exploited.